Tags

Decorator Pattern

Published Nov 18, 2019

[

In object-oriented programming, the decorator pattern is a design pattern that allows behavior to be added to an individual object, dynamically, without affecting the behavior of other objects from the same class. The decorator pattern is often useful for adhering to the Single Responsibility Principle, as it allows functionality to be divided between classes with unique areas of concern. The decorator pattern is structurally nearly identical to the chain of responsibility pattern, the difference being that in a chain of responsibility, exactly one of the classes handle the request, while for the decorator, all classes handle the request.

Overview

What problems can it solve?

- Responsibilities should be added to (and removed from) an object dynamically at run-time.

- A flexible alternative to subclassing for extending functionality should be provided.

When using subclassing, different subclasses extend a class in different ways. But an extension is bound to the class at compile-time and can’t be changed at run-time.

What solution does it describe?

Define Decorator objects that

- Implement the interface of the extended (decorated) object (

Component) transparently by forwarding all requests to it and - perform additional functionality before/after forwarding a request

This allows working with different Decorator objects to extend the

functionality of an object dynamically at run-time.

Intent

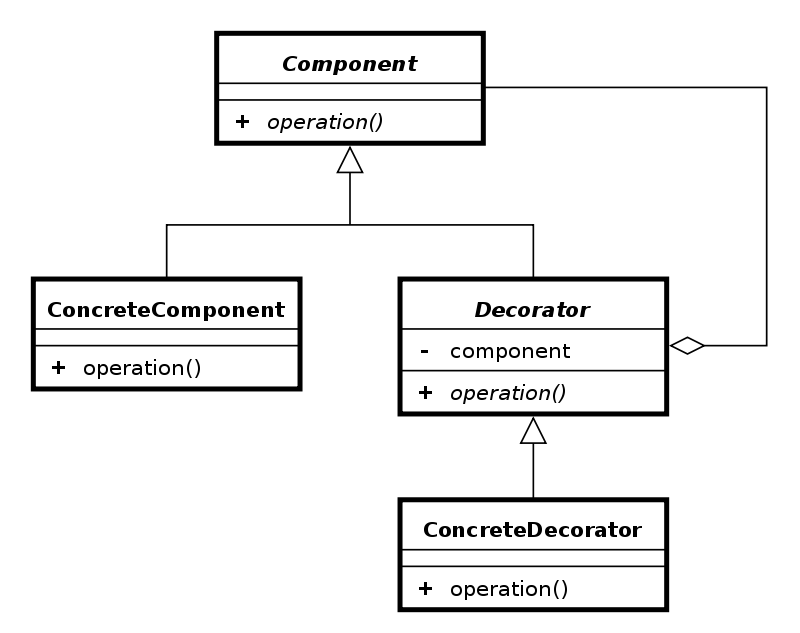

The decorator pattern can be used to extend (decorate) the functionality of a certain object statically, or in some cases at run-time, independently of other instances of the same class, provided some groundwork is done at design time. This is achieved by designing a new Decorator class that wraps the original class. This wrapping could be achieved by the following sequence of steps:

- Subclass the original Component class into a Decorator class;

- In the Decorator class, add a Component pointer as a field;

- In the Decorator class, pass a Component to the Decorator constructor to initialize the Component pointer;

- In the Decorator class, forward all Component methods to the Component pointer; and

- In the ConcreteDecorator class, override any Component method(s) whose behavior needs to be modified.

This pattern is designed so that multiple decorators can be stacked on top of each other, each time adding a new functionality to the overridden method(s).

Note that decorators and the original class object share a common set of features. In the previous diagram, the operation() method was available in both the decorated and undecorated versions.

The decorator pattern is an alternative to subclassing. Subclassing adds behavior at compile time, and the change affects all instances of the original class; decorating can provide new behavior at run-time for selected objects.

Motivation

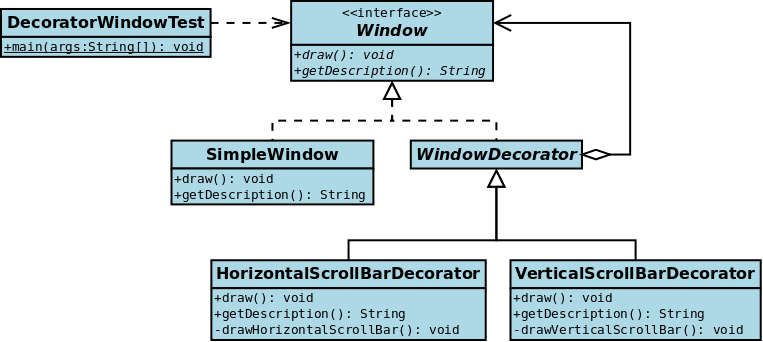

As an example, consider a window in a windowing system. To allow scrolling of the window’s contents, one may wish to add horizontal or vertical scrollbars to it, as appropriate. Assume windows are represented by instances of the Window interface, and assume this class has no functionality for adding scrollbars. One could create a subclass ScrollingWindow that provides them, or create a ScrollingWindowDecorator that adds this functionality to existing Window objects. At this point, either solution would be fine.

Now, assume one also desires the ability to add borders to windows. Again, the original Window class has no support. The ScrollingWindow subclass now poses a problem, because it has effectively created a new kind of window. If one wishes to add border support to many but not all windows, one must create subclasses WindowWithBorder and ScrollingWindowWithBorder etc. This problem gets worse with every new feature or window subtype to be added. For the decorator solution, we simply create a new BorderedWindowDecorator - at runtime, we can decorate existing windows with the ScrollingWindowDecorator or the BorderedWindowDecorator or both, as we see fit. Notice that if the functionality needs to be added to all Windows, you could modify the base class and that wil do. On the other hand, sometimes (e.g., using external frameworks) it is not possible, legal, or convenient to modify the base class.

Note, in the previous example, that the “SimpleWindow” and “WindowDecorator” classes implement the “Window” interface, which defines the “draw()” method and the “getDescription()” method, that are required in this scenario, in order to decorate a window control.

Usage

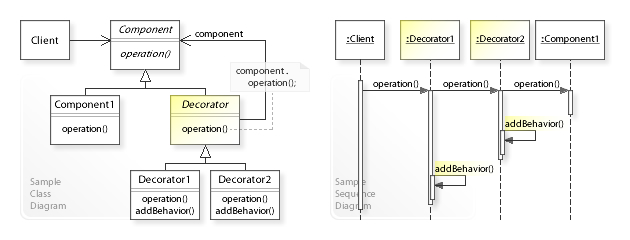

In the above UML class diagram, the abstract Decorator class maintains

reference (component) to the decorated object (Component) and forwards all

requests to it (component.operation()). This makes Decorator transparent

(invisible) to clients of Component.

Subclasses (Decorator1, Decorator2) implement additional behavior

(addBehavior()) that should be added to the Component (before/after

forwarding a request to it).

The sequence diagram shows the run-time interactions: The Client object works

through Decorator1 and Decorator2 objects to extend the functionality of a

Component1 object.

The Client calls operation() on Decorator1, which forwards the request to

Decorator2. Decorator2 performs addBehavior() after forwarding the request

to Component1 and returns to Decorator1, which performs addBehavior() and

returns to the Client.

Examples

C++

Two options are presented here, first a dynamics, runtime-composable decorator (has issues with calling decorated functions unless proxied explicitly) and a decorator that uses mixin inheritance.

Dynamic Decorator

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

struct Shape {

virtual ~Shape() = default;

virtual std::string GetName() const = 0;

};

struct Circle : Shape {

void Resize(float factor) { radius *= factor; }

std::string GetName() const override {

return std::string("A circle of radius ") + std::to_string(radius);

}

float radius = 10.0f;

};

struct ColoredShape : Shape {

ColoredShape(const std::string& color, Shape* shape)

: color(color), shape(shape) {}

std::string GetName() const override {

return shape->GetName() + " which is colored " + color;

}

std::string color;

Shape* shape;

};

int main() {

Circle circle;

ColoredShape colored_shape("red", &circle);

std::cout << colored_shape.GetName() << std::endl;

// Won't compile, since |Resize| is not accessible from |ColoredShape|.

// colored_shape.Resize(1.2);

}

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

struct WebPage

{

virtual void display()=0;

virtual ~WebPage() = default;

};

struct BasicWebPage : WebPage

{

std::string html;

void display() override

{

std::cout << "Basic WEB page" << std::endl;

}

~BasicWebPage()=default;

};

struct WebPageDecorator : WebPage

{

WebPageDecorator(std::unique_ptr<WebPage> webPage): _webPage(std::move(webPage))

{

}

void display() override

{

_webPage->display();

}

~WebPageDecorator()=default;

private:

std::unique_ptr<WebPage> _webPage;

};

struct AuthenticatedWebPage : WebPageDecorator

{

AuthenticatedWebPage(std::unique_ptr<WebPage> webPage):

WebPageDecorator(std::move(webPage))

{}

void authenticateUser()

{

std::cout << "authentification done" << std::endl;

}

void display() override

{

authenticateUser();

WebPageDecorator::display();

}

~AuthenticatedWebPage()=default;

};

struct AuthorizedWebPage : WebPageDecorator

{

AuthorizedWebPage(std::unique_ptr<WebPage> webPage):

WebPageDecorator(std::move(webPage))

{}

void authorizedUser()

{

std::cout << "authorized done" << std::endl;

}

void display() override

{

authorizedUser();

WebPageDecorator::display();

}

~AuthorizedWebPage()=default;

};

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

std::unique_ptr<WebPage> myPage = std::make_unique<BasicWebPage>();

myPage = std::make_unique<AuthorizedWebPage>(std::move(myPage));

myPage = std::make_unique<AuthenticatedWebPage>(std::move(myPage));

myPage->display();

std::cout << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Static Decorator (Mixin Inheritance)

This example demonstrates a static Decorator implementation, which is possible due to C++ ability to inherit from the template argument.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

struct Circle {

void Resize(float factor) { radius *= factor; }

std::string GetName() const {

return std::string("A circle of radius ") + std::to_string(radius);

}

float radius = 10.0f;

};

template <typename T>

struct ColoredShape : T {

ColoredShape(const std::string& color) : color(color) {}

std::string GetName() const {

return T::GetName() + " which is colored " + color;

}

std::string color;

};

int main() {

ColoredShape<Circle> red_circle("red");

std::cout << red_circle.GetName() << std::endl;

red_circle.Resize(1.5f);

std::cout << red_circle.GetName() << std::endl;

}

References: